By volunteer Katy Elliott, With contributions from School of Sexuality Education’s Dr Emma Chan.

During School of Sexuality Education's workshops, students ask us questions about virginity, and these largely come from a heteronormative perspective. In this piece, School of Sexuality Education volunteer Katy Elliott explores this perspective and why re-defining 'virginity' is important for all.

When I was a teenager, ‘virginity’ felt like quite a big deal. I spoke to my friends about ‘losing it’ and I worried I would be the last ‘virgin’ left. I thought ‘losing your virginity’ meant having penis-in-vagina sex and nothing else would count. I’d heard about the ‘hymen’ and worried that when I did have sex, I would bleed and it would be embarrassing. Quite frankly, virginity and sex made me anxious and scared.

I wish I’d had lessons from School of Sexuality Education to set things straight.

At School of Sexuality Education, we work to dispel the myths surrounding the traditional understanding of ‘virginity’. We help young people understand that sex means different things to different people and there is no right or wrong way to have it. We encourage people to do what feels right for them (and any partner/s) and not feel pressured into anything. And we try to deconstruct ideas around ‘virginity’ which can be heteronormative and contribute to gender inequality.

So, what is a social construct?

Put simply, a social construct is an idea created by society. It’s not always something concrete we can see, like rivers, mountains and oceans. Instead, social constructs are how we humans make sense of the world. Social constructs are driven by the ideas and beliefs which exist in our societies. The pressures, myths and expectations surrounding the traditional idea of ‘virginity’ are very much the product of norms and ideas created by us humans.

Why is the social construct of virginity damaging?

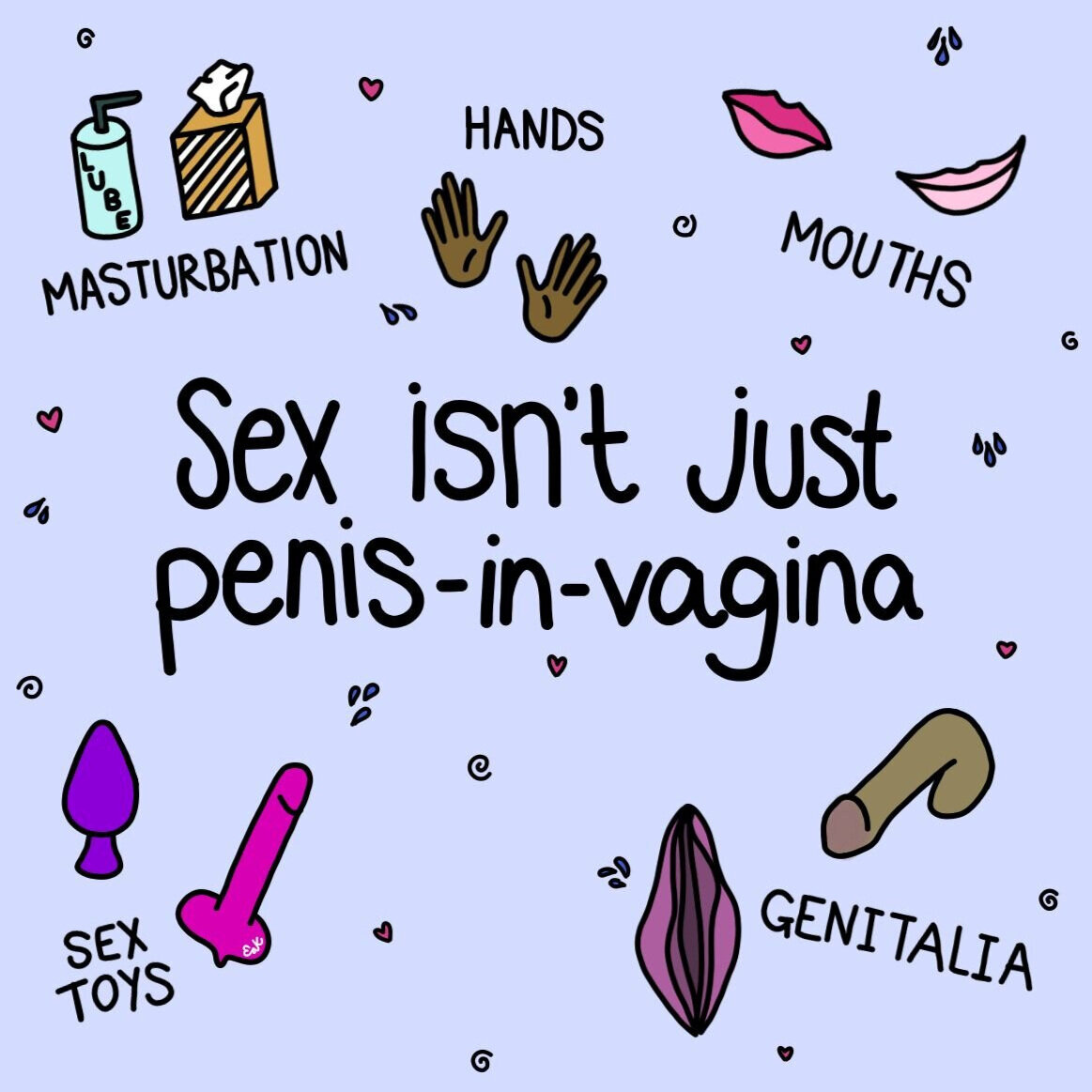

1. The focus on penis-in-vagina sex erases other experiences.

Contrary to what the traditional understanding of virginity would have you believe, penis-in-vagina sex is not the only way to have sex. Human beings are a glorious variety of wants, needs and preferences. Sex can mean very different things to different people. The most important thing is doing what feels right for you.

School of Sexuality Education's definition of sex is 'anything that makes you feel horny or aroused'. This means that sex doesn't just have to be between a man with a penis and a woman with a vulva. It can take place between people of varying genders - the same or different to each other. It can take place between people with different or the same types of genitalia, even using different body parts. What makes some people 'horny' might not even involve genitalia (or other people) at all. Examples of sexual activities for some people include oral sex, anal sex, kissing, cuddling, massages, masturbation, and hand-play!

The traditional concept of virginity buys into the idea that the only type of sex that 'counts' is penetrative penis-in-vagina. This ignores the preferences, desires and lived sexual experiences of many people. In doing so it enforces a very particular heteronormative idea of sex and relationships on society.

In addition, many people with a vulva and vagina don’t orgasm from penetrative sex, and get the most pleasure from clitoral stimulation. But because our understanding of what it means to have sex is shaped by this idea of virginity, it’s often thought penis-in-vagina sex is the ‘main’ way to have sex, with the result that people don’t explore other parts of their body, for example the clitoris. Many miss out on a lot of pleasure because they don’t understand that other types of sex exist.

I’ve said it once, but I’ll say it again - the most important thing to remember here is that sex exists in many different wonderful forms and no single type of sex is the most important or valid. Regardless of your sexuality or gender, sex and pleasure is yours to define and experience in whatever way is best for you.

2. The association between purity and virginity serves to police women’s bodies

The idea of virginity equating to moral and personal purity has long been used to control some bodies - usually those seen as female, through a lens of gender as both binary and fixed. Examples of this can be found within ‘Purity Culture’. I spoke to my friend Katie Brookfield, an expert in this area, to give us her thoughts:

Virginity has long been a key factor in determining a ‘woman’s worth’ and therefore their bodies are heavily policed. The emphasis on virginity emerged as our ancestors moved from communal, hunter-gatherer communities to land-owning societies. Keeping land meant having (male) heirs, and therefore it was imperative that there be no question of parentage. The solution? Ensure that a wife or concubine is a ‘virgin’ to secure a pure lineage, land and, ultimately, power.

My particular area of study is around the relationship between religion and sexuality. From Abraham to abstinence pledges, virginity has been a focal element of a woman’s purity and, consequently, their value. Whilst sexual purity has long been associated with religion - in many ways because of the link between holiness and asceticism - it is in recent years that it has taken on a whole new dimension. Pervasive within the conservative Christian community, ‘purity culture’ has infiltrated not just churches, but schools, healthcare providers and even governments.

Proponents of purity culture are concerned with both physical and emotional purity, only allowing for two rigid, contrasting gender roles. There is a heavy emphasis on the purity of women and their responsibility to keep male counterparts from ‘stumbling’. They are both controlled by and the gate-keepers of this concept of purity. Physical appearance is heavily monitored, with strict rules on modest dress for young women who have to be aware of their hemline, neckline and even their eyeliner, to ensure men do not look at them lustfully.

Young people are told to flee from the hypothetical ‘how far is too far’ line, yet this again is the responsibility of the woman. Men are painted as uncontrollable creatures who rely on a pure woman to keep their raging sexuality under wraps until the wedding night - an idea which contributes significantly to rape culture, FYI. Women, on the other hand, are taught nothing of pleasure and desire, but are instead told to ‘guard their heart’. They need to be as vigilant about guarding their emotional virginity as they are their physical. Why? Because whether physical or emotional virginity, a woman gives away a piece of her heart each time. She becomes damaged goods; a used, impure woman unable to give her whole self to her future husband. This ‘purity myth’ controls every aspect of a woman’s body: what they wear, what they think, and what they let between their legs.

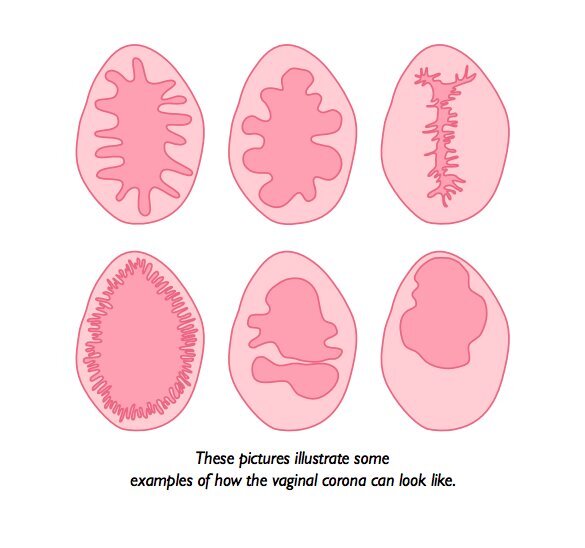

3. The hymen is a myth

Like many people, I thought a hymen was a stretchy piece of cling film-like membrane which covered the vaginal opening. I thought it was the same for everyone and you could break it by inserting a tampon, riding a horse, or having penis-in-vagina sex. Turns out that isn’t the case.

RFSU, a Swedish sex education charity actually prefer the term ‘vaginal corona’ which has no hymen-related myths associated with it. The vaginal corona is made up of folds of tissue and comes in lots of different shapes and sizes. If you deliver a baby vaginally, it can change and become less visible. And in very rare cases, it can cover the vaginal opening completely, requiring medical assistance because period blood can’t leave the body.

The link between hymens and virginity is a social construct. You can’t tell if someone has had sex by looking at their genitalia - the shape and size of the vagina doesn't change size with penetrative sex, nor does the hymen change from penis-in-vagina sex. You may have heard US rapper T.I. 's comments about accompanying his daughter to the gynaecologist each year to check her hymen (and therefore virginity) was still intact. This statement – quite rightly – caused outrage, not least because the practice of ‘virginity testing’ is condemned by the United Nations as a type of violence against women and girls. And also because what this young person decides to do with their body has absolutely nothing to do with their parent.

In the book Vagina: A Re-education, Lynn Enright discusses how the incorrect belief that people with a vulva will bleed the first time they have sex can be very dangerous. In some cultures, if a person with a vulva does not bleed when having penis-in-vagina sex with their husband for the first time, this is seen as shameful. It can even be used to excuse violence against this individual. Because of this, some doctors in the UK and throughout the world offer ‘hymen repair’ procedures. The procedure involves stitching together vaginal tissue, which will break and cause bleeding upon penetrative sex. As with any surgery, this procedure comes with some risks. It’s also completely unnecessary from a medical perspective, existing purely because of social beliefs which mean it’s expected for a person with a vulva to bleed on their wedding night.

A new social construct?

Social constructs are shaped by human ideas and beliefs. They exist due to human ideas and beliefs. And they continue to exist because humans keep spreading these ideas and beliefs. In the case of virginity, this can be through sex education which puts a lot of focus on penis-in-vagina sex. It can be through religious and cultural ideas which are passed down through generations. It can be through portrayals of sex in movies and porn. And the dominant views and beliefs often win out, sometimes making social constructs resistant to change.

So maybe it’s time that we took charge and actively shaped the social construct of virginity for the better. By teaching young people that sex (and therefore virginity) means different things to different people. By acknowledging that all experiences of sex are valid. And the most important thing? That if, how and when you have sex has nothing to do with anyone else and everything to do with what’s right for you - and any sexual partner/s, of course.

**We have an online worksheet all about The Virginity Myth using teachable moment from Netflix’s ‘Sex Education’ (suitable for 16+) here.

Illustrations by Evie Karkera, unless otherwise credited.

Our book ‘Sex Ed: An Inclusive Teenage Guide to Sex and Relationships’ is out now.