School of sexuality education’s Almaz Ohene explores how internet policies around sexuality are consistently implemented in favour of straight, white, cis male ideas of acceptability

A couple of months ago, in July 2020, the School of Sexuality Education Instagram account was blocked and disabled.

We received a message from Instagram stating that the account had been deactivated for not following ‘Community Guidelines’ because ‘sexually suggestive content isn’t allowed on Instagram’. This includes ‘posting sexually suggestive photos or other content; soliciting sexual services; using sexually explicit language.’ There was no specific information regarding which post(s) were problematic for Instagram, nor was there any warning of the deactivation. Considering the fun, educational tone of our account, the use of anatomically correct language, and the fact that most of our posts are illustrations this was baffling.

School of Sexuality Education reported this deactivation as an error but heard nothing from Instagram for a week. We went on to report it through Report Harmful Content who contacted their industry partners. After that our account was reactivated but with no further explanation.

Both the team, and wider supporters of the work we do at School of Sexuality Education, were outraged. That Instagram had deemed the vital Sex Education work we do, to be in breach of the community guidelines, without specifiying what exactly it was that breached them, was beyond frustrating.

A number of independent studies have shown that internet policies around sexuality are consistently implemented in favour of straight, white, cis male ideas of acceptability, and that the censorship of benign Sex Education content on social media platforms is disproportionately harming marginalised communities.

How? Well, automated moderation, or algorithmic models, are used on a huge scale to automatically sort through content posted to social media platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, TikTok etc. Facebook’s algorithmic model, for example, has now been programmed to spot commonly used emoji strings – such as the eggplant or peach emoji – which are commonly used to refer to fun sex acts or indicate certain sexual preferences.

Often, social media platforms will ‘shadowban’ – when a social media platform hides content from the algorithm with tactics such as making them invisible in the hashtags, banning liking/commenting, or continuously censoring their content – accounts using vocabulary or hashtags deemed unacceptable.

This means sex educators can’t even use code to talk about the pleasurable aspects of sex, or help LGBTQ+ people find information via hashtags, even when the content is non-explicit.

Salty, an online newsletter and platform for women, trans and non-binary people, conducted some research in 2019, which reported that that plus-sized profiles were often flagged on Instagram for “excessive nudity” and “sexual solicitation”, and concluded that “risqué content featuring thin, cis white women seems to be less censored than content featuring plus-sized, black, queer women.”

It also found that people who come under attack for identifying as a member of the LGBTQ+ community, for example, have had their accounts reported or banned instead of the attacker. And later this year, it also reported that wheelchair user Alex Dacy (a.k.a. @wheelchair_rapunzel) had her picture, below, banned, even though it was inspired by an accepted Kim Kardashian West photo.

It is truly saddening how common real-life structures of oppression are being replicated online through this inherently biased automated moderation and censorship. It sends a deeply upsetting message, that only homogeneity is acceptable. School of Sexuality Education’s work is focused on dismantling these norms and online communities have the opportunity to help us do this work, but instead we are forced to stick to the same tired tropes.

Facebook also does not allow the mention of sexual pleasure in adverts for contraceptives. Instead, the focus must be “on the contraceptive features of the product.” A dichotomy exists because a cis man’s ability to have an erection is considered a health concern, based on the biological fact that a man must orgasm in order to procreate. As a result, male sexual wellness brands are considered morally acceptable as ‘family planning products’. Women, however, don’t need to experience an orgasm in order to procreate, so any information that exists solely to grant women pleasure is considered a ‘vice’ by Facebook.

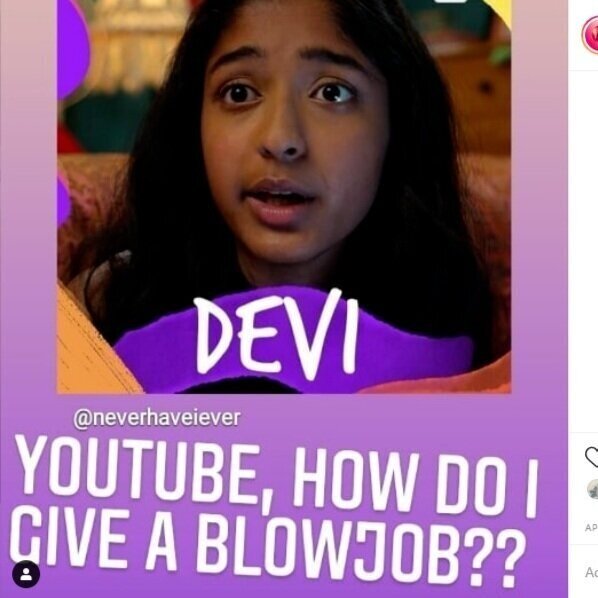

This academic year sees Sex and Relationship Education become compulsory for all schools in England for the first time, hooray! But without being able to voice questions about the topic on social media, – which, as we know, is where young people spend a large proprtion of their time – they will still be left with the misconception that anything sex-related is taboo. And that’s the opposite of our ethos here at School of Sexuality Education. Social media bods, this is getting really tired – sort it out!

Illustrations by Evie Karkera, unless otherwise credited.

Our book ‘Sex Ed: An Inclusive Teenage Guide to Sex and Relationships’ is out now.